For the past 3 years I’ve been making regular trips to the Araucaria forests of the southern Andes in Chile. I first encountered these remarkable forests in 1977, during an extended 6 month trip throughout the southern countries of South America, when someone I met mentioned there was an interesting forest on the pass between the Argentinian town of Junin de los Andes and Pucon in Chile. As I was planning to cross from Argentina to Chile, I decided to take that route, and discovered that what he had referred to was a whole forest of what I knew from Scotland as the monkey puzzle tree.

That common name is a fanciful misnomer of course, as there are no monkeys that occur this far south in South America, but it was used to describe the difficulty any primate would experience in attempting to climb the tree that is known in scientific terms as Araucaria araucana. With a dense concentration of tough, sharply pointed triangular leaves on its branches, the tree is difficult to even touch without getting pricked as though by a cactus, so no vertebrate creature climbs these trees at all.

British explorers brought seeds of the Araucaria back to the UK at the end of the 18th century, and once young trees began growing they became a botanical curiosity, attracting considerable interest and being planted out in town parks, gardens and the grounds of stately homes. My first encounter with one was in the grounds of the boarding school I went to in rural Perthshire in the 1960s, and I remember being intrigued by its unusual leaves and branching structure. When I then encountered the forest of these trees in 1977, it was exhilarating, and almost overwhelming, to see so many of them all together.

That trip to the southern Andes, over 40 years ago, strengthened my interest in the Araucaria tree, and during another journey to Chile in 1998 I spent a couple of days in the forests near the town of Pucon. I didn’t have an opportunity then to extend my time there, but I knew that one day I would return for a longer visit. So it was that in January 2015 I went back to southern Chile, with two weeks set aside specifically to explore the Araucaria forests. (the final week of that trip involved visiting Pumalin Park further south in Chile’s fiord country, which I wrote about in my memorial blog about Doug Tompkins).

That proved to be a pivotal experience for me, as I was able to immerse myself in the forest with the benefit of all the ecological knowledge I had learned from my work in Scotland with the Caledonian Forest. This enabled me to gain a deep understanding of, and appreciation for, this remarkable ecosystem of Araucaria trees and all their associated species.

In the UK and other countries where it has been planted, such as Japan and the western USA, the Araucaria is usually seen as individual specimens or occasionally in small groups, but in its natural habitat it is a keystone species in a fascinating ecosystem. Many of the trees are festooned with old man’s beard lichens (Protousnea spp.), and the forest understorey is often dominated by bamboo (Chusquea culeou). The main dispersal agent for the Araucaria’s seeds is the most southerly parrot in the world, the cachaña or austral parakeet (Enicognathus ferrugineus), and the most southerly-occurring hummingbird, the green-backed firecrown (Sephanoides sephaniodes), acts as a pollinator for many of the plants in the forest.

The Araucaria tree occurs both in single-species stands, and in mixed forests with trees from the southern beech genus, Nothofagus. Several of those are deciduous, including lenga (Nothofagus pumilio) and ñire (Nothofagus antarctica), and they bring beautiful colours to the landscape in the autumn, making a dramatic contrast with the evergreen foliage of the Araucaria itself. Another tree commonly found with the Araucaria is coigüe (Nothofagus dombeyi), which retains its leaves throughout the year.

The Araucaria tree is one of the most easily-recognisable and distinctive trees in the world today. Its straight, columnar trunk, umbrella-shaped crown and rigid triangular scaly leaves give it a unique appearance and charismatic presence in the volcanic landscapes where it occurs. Growing to a height of 50 metres, it towers over the broadleaved trees in the forest, and individual trees can live for over 1,000 years. It is also one of the most ancient tree species in the world, having co-evolved with the dinosaurs in our planet’s distant past. While it’s sometimes described as a relict species, an anachronism from the bygone era of giant reptiles, it is in fact one of the greatest success stories in the plant kingdom — it is an iconic tree that has stood the test of time. Millions of years ago it developed features that enabled it to thrive in conditions that were very different from those of the world today.

Those evolutionary adaptations have been so effective that they have not only ensured the continued existence of the species for more than 60 million years, but also have resulted in the fact that even now there are relatively few organisms that are able to exploit the tree. Another feature of the Araucaria tree is that it is a fire-adapted species, with a thick bark that enables it to thrive in an area of ongoing volcanic activity and where there are regular fires.

It also has specially-strengthened bases to its branches, with a high resin content in them. Known in Spanish as picoyos, they are an evolutionary adaptation to cope with the heavy weight of snow that accumulates on the branches during the region’s cold winters, when there is an average of 2 metres of snowfall each year. Because of the resin, the picoyos persist long after the rest of a dead Araucaria’s wood has rotted away and they become fossilised quite readily. As such, the old picoyo wood has become a prized material for local artisan craftsmen for wood carving purposes.

The Araucaria tree is a dioecious species, meaning that individual trees are either male or female, and one of each sex is required for pollination and seed production to occur. Although hermaphroditic trees (ie individuals with both male and female reproductive organs on them) are found, these are quite rare. One consequence of this is that in countries like the UK where individual Araucarias have been planted as specimen trees, they will not produce any seeds, unless another tree of the opposite sex is in relatively close proximity, so that pollination can take place.

Male pollen cones release their pollen in the late spring, and fertilised female seed cones reach maturity 18 months later, in the autumn of the following year. Pollination is by the wind, and mature seed cones are large, with a diameter of 20 cm. and weighing up to 4.5 kg. Each one contains up to 200 seeds, or piñones, as they are known in Spanish.

The piñones are 3- 5 cm. in length and taper to form a wedge-like shape, with a curved scale at their thicker end. They are grouped radially in the cones, which have a central, cylindrical core that the seeds are attached to. After the seeds have fallen , or have been eaten, these cores remain visible on the trees until the remnant cones disintegrate fully and fall to the ground.

The closely-related ancestors of the Araucaria tree are thought to have co-evolved with the sauropod, or long-necked, dinosaurs, with the remarkable body shapes of those ancient reptiles enabling them to reach the trees’ cones, at the tips of their highest and outermost branches. Today, the main dispersal agents for the Araucaria’s seeds are two avian descendants of the dinosaurs – the cachaña, or austral parakeet (Enicognathus ferrugineus), and the rarer choroy or slender-billed parakeet (Enicognathus leptorhynchus). These gather in noisy squawking flocks in the autumn, breaking open the cones and eating some of the piñones. As they do so, many of the seeds fall untouched to the ground, where they are harvested by rodents such as the long-haired grass mouse (Abrothrix longipilis). These small mammals cache the piñones by burying them, and never recover all of them, thereby enabling some to germinate and grow on as a new generation of young trees.

Here’s a short video clip of some austral parakeets feeding on the piñones in the canopy of an Araucaria tree:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PeOvzxHQm48;vq=hd720&rel=0&showinfo=0

The piñones are highly nutritious, and during my first experience of the Araucaria forest in the southern autumn of 1977, I cooked and ate some myself.

In the past they were a staple food of the local indigenous people, who call the tree pehuén, and themselves the Pehuenche, meaning literally ‘people of the Araucaria tree’ in their own language, Mapudungun. Their culture was centred around the tree, and they ate the piñones raw, boiled and roasted, or ground into flour, and also used them for making an alcoholic drink. Resin obtained from incisions in the tree’s trunk was used in the treatment of ulcers and wounds, while the skin of the piñones was used as a dye. Today the piñones are still widely consumed as a food, both by the Pehuenche and by Chileans of European origin, and they are readily available in vegetable markets in the autumn.

I was deeply touched by the two weeks I spent in the Araucaria forest in January 2015, during the height of the summer there. I spent several nights out in my tent, camped amongst the trees near Lanín Volcano, the highest of the seven volcanoes that occur within the natural range of the Araucaria tree in the Andes. I walked amongst the trees by the starlight of the Milky Way in the middle of the night, and felt the pulse of life in the trunks of trees that were hundreds of years in age. I got to really know the trees and many of the other species in the forest and felt a deep connection with the life, vitality and diversity of this remarkable ecosystem.

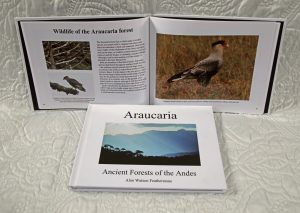

From that connection I felt an inner prompting, just as I had done in the early 1980s with the Caledonian Forest in Glen Affric in Scotland. It seemed to me as though I was being called upon to act on my love for, and fascination with, the Araucaria tree and the forests where it naturally occurs. I felt inspired to use my ecological understanding and knowledge, together with my talent as a photographer, to bring greater public awareness to the tree and the threats which it is currently facing. Thus was born the idea to produce a high quality photographic book, with detailed ecological text, about the Araucaria Forests of the Andes.

Since that visit in 2015, I’ve made four further trips to the Araucaria region of Chile and Argentina, to get to know the forest better, and to experience it in all the seasons of the year. My passion for it has increased with every visit, and I’ve made some interesting discoveries along the way, which I’ll write about in future blogs. I’ve also begun work on the book, and have produced a few sample copies, showing what it could look like. In the coming months my focus will be on completing the writing and compilation of the book, with the aim of getting it published by the end of 2018.

To finish this blog, here’s some video footage from a magical day I spent in the Araucaria forest of Villarrica National Park near Lanín Volcano in late April 2016. The deciduous trees were at the peak of their autumn colours and it had been raining for a while, and then, remarkably it turned to snow ….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kx44OxZSyHw;vq=hd720&rel=0&showinfo=0

I am glad you appreciate these wonderful trees.

I have a question….

I had two monkey puzzles in front of my house. One male & one female. The female produced abundant seeds every summer, till we had to have it felled a couple of years ago. Sadly, it was starting to die, but till that point we had collected the seeds and sold them to various nurseries round the UK.

Two years later, the male has started to produce seeds. This has never happened before. If it had we would have noticed – or my children would have, because this was an important source of pocket money!

I understand that hermaphroditism in monkey puzzles is not unknown, but is it usual for a tree to change from male to hermaphroditic? They were both about 120-130 years old.

I would love to know.

Alan: Nice to read of your current project. They are indeed fascinating and glorious trees and your book will be a welcome addition to the libraries of Chile and beyond. The link with the coigue, lenga, and nire, is very interesting. We have planted all of those species in our little forest, but it also explains the reason why CONAF, the forestry service, has begun planting them in this region… although to be honest I am not sure of the wisdom in this as we don not seem to have any Araucaria growing naturally where we live. Next time you visit Chile, please consider visiting us here in Aysen, to see and experience what we are up to and the wonderful nature of where we live. We have a nice little guest cabin and recently planted , and naturally regenerated forested garden for you to enjoy. The Austral Parakeets are also regular visitors to our land and it’s nice to know where they may fly off to when they leave our land.

Hi Paul,

Thanks for your comment on my blog. It’s nice to hear from you, and I wasn’t aware that you’re living in Chile now. How long have you been there? Thanks for the invitation to visit Aysen – it’s one region of Chile I’ve not been to yet. The closest I’ve been is Chaiten to the north, and Puerto Natales and Torres del Paine to the south.

Aysen is well outside the natural range of the Araucaria tree, which is why you don’t have any there. The tree occurs naturally in just the La Araucania region, so although you’ve got lenga, ñire and coigüe where you are, the absence of Araucaria is no surprise at all. Lenga and ñire occur all the way down to Tierra del Fuego and the smaller islands south of it, whilst the coigüe of further north (Nothofagus dombeyi) is replaced by the coigüe de Magallanes (Nothofagus betuloides) there.

With best wishes,

Alan

Es ist ja erstaunlich hier zu erfahren, dass es sozusagen Internet-Humboldte etc gibt. Muss das erst mal verarbeiten. Melde mich wieder. Rahimo Barbara Kempe.

Hi Alan! I have been intrigued by these ancient trees for some time, after my experiences with the Scottish pinewoods and childhood fantasies about dinosaurs. Some really amazing images here as always, totally transfixing. Autumnal shot with the two tress and distant tree studded hill- beautiful, evoking that Chinese Landscape painting aesthetic that can be found in Scotland, reminds me of Glen Strathfarrar. Also the image looking through the snow laden boughs into the green golden branches, the swooping forms and glowing light are mesmerising. The milky way image of deep space and ancient species is a window into the past – i suppose they all are.

Really amazing.

I’m currently in China and visiting Huashan tomorrow, which has some stunted twisted pines from what I gather, hopefully will get to the Huangshan pines and cliffs in July.

Looking forward to seeing the other treasures you found there.

Hi Kyle,

Thanks for the positive feedback about this blog – there will be some more about the Araucaria forest coming soon.

I’m envious of you going to visit the Huangshan pines, as I’ve seen many photos from there over the years (and used some in the Trees for Life Engagement Diary when it had an international focus). I’m sure you’ll have a fantastic time when you go there in July!

With best wishes,

Alan

Fantastic blog — what a beautiful forest and amazing ecosystem. And that is just one example of various ecosystems around this amazing planet

Great pictures — look forward to the book

Many thanks for the feedback, John – there’s more beauty and remarkable parts of the Araucaria ecosystem coming up in some other blogs.

With best wishes,

Alan