For a casual visitor, it may often appear like there’s not much to see in the Caledonian Forest in winter. By then, all the leaves have fallen from the deciduous trees, many birds have migrated south for the winter and insects have gone into pupal stasis, out of sight. My experience, however, is that there is in fact still plenty of interest in the forest, if I shift my focus to some of the permanent, year-round life forms, and take time to look closely for them.

In a period of just over a week in mid-December I made three trips out to Glen Affric – two of them focussed on practical forest restoration projects we’re planning there, and the third one a dedicated photo trip on a Sunday. All three days were overcast, damp and windstill for the most part, making them ideal for much of the photography I like to do in the forest. This blog contains a combination of images from those trips, and on the first of those my attention was drawn straightaway to the arboreal lichens on the downy birch trees (Betula pubescens) in particular.

Although these lichens are on the trees all year, they are much more obvious in winter, after the trees’ leaves have fallen, and particularly on damp days, when they are fully hydrated and vibrant with life.

I’ve described them before as being like the ‘leaves’ of winter, because of their abundance on the broadleaved trees in particular. As epiphytes, they use the trees for support, but derive no nourishment from them, relying instead on atmospheric moisture and airborne organic particles for their nutrients. Their presence in areas like Glen Affric are an indication of both the wet climate and the lack of atmospheric pollution – epiphytic lichens are highly susceptible to aerial pollutants, because they have no access to soil, and are instead dependent on clean air.

I stopped on the north shore of Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin, just past the dam, where the road bends sharply to the left and crosses the Allt Coire Beithe watercourse. On the west of that burn, the ground rises very steeply to quite a high bluff, which provides both shelter from the prevailing westerly winds and year-round shade from the sun for the vegetation growing below, on its north-east facing slope. As a result of these factors, it’s one of the best areas in the whole glen for mosses and lichens, as the absence of sunshine and strong winds helps keep the area permanently damp, creating ideal conditions for epiphytes and bryophytes (as mosses and liverworts are collectively known) to thrive.

The photos above of the lichen-encrusted trees attests to the suitably of this area for them, and the stone parapet of the bridge over the burn was almost entirely covered in places by a dense growth of mosses and lichens.

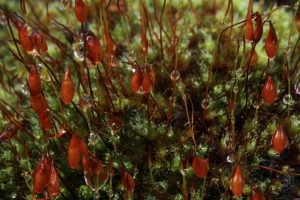

On one section of the bridge in particular there was a large colony of one of the lichens (Cladonia pyxidata) which produces cups, or podetia, as well as several clumps of moss with spore capsules (which I haven’t got identified yet).

While I was looking at the moss and lichen, I noticed a leaf that had fallen on to the parapet, in amongst some of the patches. I recognised it as being from a goat willow (Salix caprea), and I was slightly surprised as I wasn’t aware of there being any of those trees on this side of the watercourse. However, when I looked up, I saw a young goat willow growing just beside the bridge, on the upstream side of it, to the west of the burn. It was a few years since I’d last stopped in this spot, so I thought that perhaps the tree may just have been a sapling then, which may be why I hadn’t noticed it before.

I have a growing interest in willows and will soon be writing the next in our series of Species Profiles on the goat willow. Willows are the second most important tree in the UK for supporting invertebrates, after oak (Quercus petraea, in the Highlands). Also, because the pH of its bark is neutral, in contrast to birches and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), which have acid bark, goat willow supports a different, and diverse, group of lichens. In wet areas such as this these include tree lungwort (Lobaria pulmonaria), and when I looked at this young tree I saw a patch of that straight away.

It was growing beside another lichen that I also recognised – a brown lichen in the genus Nephroma (which are sometimes known as kidney lichens), and in this case the species Nephroma laevigatum.

Like tree lungwort, this kidney lichen is typically found in wet areas in the north and west Highlands, and is therefore associated with our remnant temperate rainforests. Another similarity with tree lungwort is that it includes a cyanobacterium (Nostoc sp.) as part of the lichen symbiotic organism. This is called the photobiont – that part of the lichen that photosynthesises, enabling the compound organism to utilise the energy of the sun. The fungal partner in the lichen is the one that provides the solid structure, or thallus, for the symbiotic organism. Nostoc is also able to absorb, or fix, nitrogen from the air, incorporating this essential nutrient into the physical structure of the lichen. When the lichen dies, or falls to the forest floor, the nitrogen becomes available for other plants, and this is one of the methods by which a natural forest, and especially an ancient forest (where there is an abundance of such lichens), maintains and improves the fertility of its own ecosystem.

There was another lichen on the goat willow which I recognised but didn’t know the name of. This was subsequently identified for me by the lichenologist John Douglass as being Thelotrema lepadinum. This is creamy-white in colour and is another indicator species of ancient woodlands. It is sometimes known as a barnacle lichen, because its apothecia – the parts of the lichen that release the spores of the fungal partner – look like small barnacles, or miniature volcanoes erupting from the otherwise flat surface of this crustose lichen.

Looking at this young goat willow reminded me that there was a much larger tree of the same species about 50 metres away, on the other side of the burn, so I went over to have my lunch beside it.

The lower part of the trunk of this large goat willow was almost entirely covered in moss and lichen, and there were some large patches of both tree lungwort and the kidney lichen (Nephroma laevigatum) on it. While I ate my lunch, I had a close look at various parts of the tree, including some of the low-hanging branches. The tips of those sometimes die back, and I was hoping that I might find the willow jelly fungus (Exidia recisa) on any that were there. It only took a few moments before I spotted first one of these fungi, and then quite a number of fruiting bodies on several different branches.

The willow jelly fungus fruits throughout the year, but is most obvious in winter, when there are no leaves on the trees, and on wet days, when the fruiting bodies are fully hydrated like this. On sunny days, they dry out and shrivel up to become almost invisible on the wood.

I usually come across these fungi on eared willows (Salix aurita), and have featured them in a previous blog. A closely-related species (Exidia repanda) occurs on birch trees, and I included a photograph of that in one of my blog posts last year. Liz Holden, the mycologist who helps me with fungal identifications, has written a description of both species that can be seen here.

On the ground near the large goat willow, there were some old logs from a downy birch tree, partially covered by moss. I noticed some fungi growing on one of them, and I recognised them as a species I’ve photographed before. I didn’t know what their name was, but Liz was able to identify them as being the olive oysterling (Sarcomyxa serotina). This is a species that typically fruits late in the autumn, after the first frosts, and gets its common name from the colour of its caps, which are often slightly slimy when wet.

After lunch I went back to the other side of the burn, closer to the steep bluff where the micro-climate is the wettest, to see what else I could find there. There’s a dense carpet of mosses on the forest floor and quite a few old logs from fallen trees – mainly birches and rowans (Sorbus aucuparia). On one of those, which was almost completely enveloped in moss and lichens, I spotted a patch of one of the dog lichens (Peltigera membranacea). This is a large lichen with a foliose (or leaf-like) growth pattern, and is notable for its white needle-like rhizines that protrude downwards from the underside of its thallus. It also has reddish-brown apothecia which develop on the edges of the thallus and a good example can be seen in the photograph on the right.

Like the other lichens I’d seen this day, this one was fully hydrated, and was exuberant with its spiky, punk hair-like shapes, so I spent a little while taking some photographs of the patch.

When I was at home that evening, looking at the photographs on my computer, I noticed something on the lichen in one of them that I hadn’t seen when I’d been out in the forest itself. It was a tiny invertebrate on part of the thallus, and when I enlarged the image I recognised it as being a springtail. Collembola, as springtails are formally known in biological terms, are a class of invertebrates that are different from insects. Unlike the latter, they are wingless, although they share the characteristic of having six legs.

This was a globular springtail, and it looked similar to one that I’d photographed at Dundreggan before. I suspected therefore that it was a member of the genus Dicyrtomina, and this was confirmed by Peter Shaw, an expert on Collembola who did a survey of springtails for us at Dundreggan a few years ago. By looking closely at my photograph, he was able to identify it as Dicyrtomina saundersi. In addition, he said this was the most northerly record for this species in mainland Scotland, making my find quite significant! (There are apparently only a handful of records for the species in Scotland altogether).

Of course I wasn’t aware of this while I was in the glen, so after photographing the dog lichens I continued westwards, driving further along the road on the north shore of Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin. On the other, west-facing side of the steep bluff, the glen opens up and provides a great vista of the loch, with the pinewoods flanking it on both sides. Where the road rises up, there’s an excellent view across the water, with the hills receding into the distance, particularly on an overcast day like this one.

Although it had been a very satisfying day so far, the glen still had another surprise for me. While I was looking at the forest on the north shore of the loch, I noticed that one of the birch trees still had bright yellow leaves on its upper branches.

This was quite astonishing as it was almost the middle of December, and the leaves had fallen off all the other birches at least a month before. I don’t have any explanation for why this one tree had kept them for so long, but it was certainly a delightful sight this day!

To finish this blog here’s a couple of photos taken at the end of one of the other days when I was in Glen Affric in mid-December, of the moon amongst some birch trees at dusk, when the clouds were dissipating.

Brilliant…. More astonishing and ravishingly beautiful photos and a most informative blog – as always. Looking forward to returning to the TfL fold next week.

Thanks Stephen – I’m glad you’re continuing to enjoy my blogs, and I look forward to seeing you at the Gathering at Dundreggan this week-end, and in the office in due course. Thanks for all your support for our work! With best wishes, Alan.

Absolutely fascinating photos and text. Thank you for them.

Thanks for the feedback Billy! With best wishes, Alan.

Thanks ALAN. Those lichens with their spores in the moss take me into a “fairyland forest”

Which makes me smile…such worlds within our world! Beautiful photography…could make some lovely cards with close-ups?

Hi Jude,

Thanks for your feedback on my photography- there are indeed whole miniature worlds when we look closely into nature, and it’s my joy to discover some of those and share them through my photography and these blogs. With best wishes, Alan.

Having just returned home from Grantown-on-Spey, your photos reminded me of some of the beautiful lichen I saw in Anagach woods this January

Thanks for your comment Marek. Many of the Caledonian pinewood remnants have trees covered in lichens, and Anagach, like Affric, is a good example of this.

With best wishes, Alan

Thanks for sharing this information and your terrific lichen photos! They are indeed the leaves of winter suddenly appearing here, too, on the elderberries and maples after the leaf fall!

Hi Peggy,

Thanks for your comment and feedback. With best wishes, Alan.