Each autumn I usually spend a couple of nights in Glen Affric, so that I can experience the early mornings there. At that time of year the days are often completely wind-still and the mornings in particular are characterised by mirror-perfect reflections in the lochs and the vibrant autumnal colours of the leaves on the trees. Overnight mist often lingers for several hours after sunrise, making it the most photogenic and memorable time of the year to be in the Caledonian Forest.

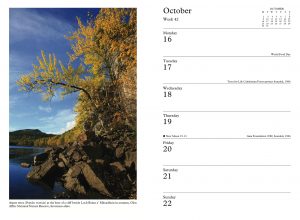

This year was no exception and on Sunday 23rd of October I had a remarkable day there. I was drawn to a group of aspen trees (Populus tremula) that are growing at the base of some cliffs on the north shore of Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin, as their leaves were at the peak of their autumn colour.

Over the years I’ve spent quite a bit of time with this particular group of aspens, usually looking at them from above, as there’s a good view over the top of them from the road on the north side of the loch. However, I’ve also scrambled down to the base of the cliffs on more than a few occasions, and the first time, about 20 years ago now, I made an interesting discovery there. I noticed some abnormal lumpy growths on several of the stems of the aspens in this stand, and was able to get them identified as being galls that were induced by a mite (Aceria populi). Most plant galls are quite ephemeral, usually only lasting until the leaves fall from the trees in the autumn, but these cauliflower galls persist for many years, being quite woody and tough in their consistency. In fact, they are still there on the aspens in this stand now, about 20 years since I first discovered them, and this is the only location where I know of them in Glen Affric, although we have over 40 aspen stands recorded there. They appear to be relatively uncommon, although I know an aspen stand in Glen Strathfarrar where they have been flourishing for many years as well.

It’s the location of these trees at the base of the cliffs that is most dramatic though, and I spent some time photographing the trees from different angles. One particular perspective, in the photograph below, is especially evocative for me, as it shows the higher ground in the distance, where our Coille Ruigh na Cuileige exclosure is located.

I took a similar version of this photograph in October 2005, when it was amongst the first images that I took just after I’d made the transition from film-based cameras to digital ones, and that version features in our new Trees for Life Engagement Diary for 2017.

If you haven’t already ordered one, copies of our diary are still available and can be ordered here. It features 58 of my photographs from many of the sites that feature in my blogs, including Glen Affric, Strathfarrar, Dundreggan, Inverfarigaig and Glen Cannich. It also contains an essay I wrote especially for it, entitled ‘Life of Pine’, which provides a unique perspective on all the life that a single Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) can sustain, and why our work to restore the Caledonian Forest is so important. If you’re looking for a last minute gift for Christmas, the diary makes an ideal choice for anyone who appreciates nature, and helps to support our work.

The aspens have survived and indeed thrived at the base of these cliffs because they are inaccessible to red deer (Cervus elaphus), which find aspen highly palatable. In the absence of overgrazing by deer, some Scots pines have also grown there successfully, along with the aspens.

On this particular morning, I was approaching the aspens from the west, following the shore line of the loch as I did so. I was still about 200 metres away from them when I spotted quite a large bird flying towards the trees and then landing on the large branch of an aspen that stretches out almost horizontally from the cliffs, over the water. I didn’t get a clear view of the bird though, and wondered if it could be a heron (Ardea cinerea), as I occasionally see them in the glen.

I began to carefully walk towards the tree, hoping that I’d be able to approach more closely without disturbing the bird and causing it to fly away. Putting my longest telephoto lens on my camera, I started taking photographs as soon as I was able to get any meaningfully-sized images of the bird, and in doing so I recognised that it wasn’t a heron at all. In fact, it was a cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo), which came as something of a surprise to me, as I’d never seen one in Affric before, and indeed it’s a species which I’ve only previously observed on the coast in the UK.

What was even more remarkable though was that the cormorant had picked an ideal spot to perch on the tree, in amongst the brilliant yellow-gold leaves of the aspen and with a superb backdrop of the ancient Scots pines of the Caledonian Forest on the other shore of the loch. As a photographer I couldn’t have asked for a more photogenic combination, and it felt like a very special privilege indeed to have this experience – a real gift of nature. The cormorant seemed completely unfazed by my presence, moving around on the branch and occasionally spreading its wings to let them dry, in what is very typical behaviour for this species.

As I watched, I saw that the cormorant was assiduous in preening itself, and it also turned around on the branch a couple of times, so that it had a view in both directions along the loch.

I was fascinated to watch the bird, as I’d never had an opportunity to study the behaviour of a cormorant like this before. In between looking at it, I took a lot of photographs, in the knowledge that if I took enough, I should manage to get a few good ones. Most of my photography is of landscapes, trees and plants, which do not move by themselves, so it is relatively straightforward to take a good image. Photographing wildlife is a different matter entirely, especially when the subject is as active as this cormorant was, hence the reason for taking plenty of images.

Observing that the bird was seemingly unconcerned by my presence, I decided to try and get closer to it, in order to take some more detailed photographs. I felt that I couldn’t just walk along the shore of the loch though, as that would run the risk of causing the cormorant to fly away. The only option was to clamber through the dense stand of trees on the steep slope at the base of the cliffs, keeping relatively hidden from the bird as I did so. It was quite an arduous route, and I had to take it carefully, in order to avoid making a lot of noise.

Over a period of 15 minutes or so I gradually made my way through the tangle of tree trunks and low branches, finally reaching a rocky ledge at the base of the cliffs, where I could go no further. My view of the cormorant had been mostly quite obscured by the trees, but fortunately when I reached the ledge, there were a few gaps in the branches that provided enough space for me to get some photographs of the bird, which now almost entirely filled the viewfinder of the camera. It was really exciting and quite exhilarating to be this close to it!

I had to take great care in setting up my tripod and putting the right lens on my camera, in order to avoid making a noise or any rapid movements that would scare the cormorant away. The bird was well aware of my presence, as it looked at me intermittently, but it seemed unconcerned by my proximity to it.

After a few minutes, and having taken lots of photographs, as well as some video footage, I began to relax, realising that the cormorant had accepted my presence so close to it. I watched it for quite some time, and even took the opportunity of having my lunch while I enjoyed observing its behaviour. Eventually, however, it took off along the loch, and I imagined that it too had gone for lunch, looking for a fish to catch. I didn’t see where it went exactly, because the trees around me obscured my view, but I felt a tremendous sense of gratitude, for having watched it for about an hour and a half altogether.

Packing up my equipment, I decided to continue along the base of the cliffs, past the rest of the aspen trees, before climbing up the gentler slope beyond them, to reach the higher ground above. Once there, I doubled back towards the west, to get a view from above the aspens, across Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin to the peninsula that extends from the south shore almost all the way across the loch. This is one of my favourite views in the whole of Glen Affric.

I’ve taken photographs here many times over the years, but on each occasion when I return to this spot, the landscape is slightly different. It varies from one season to another, and even between (for example) one autumn and the next – the leaves change colour at a slightly different time each year, and with a varied intensity of colour.

While I was photographing the aspens, I noticed a fallen leaf on the ground that was mostly yellow, but had a wedge of green colour remaining in between two of the veins. I recognised this immediately as being the work of a micro-moth called the aspen green island leaf miner (Ectoedemia argyropeza). The adult female of this moth lays an egg on the surface of the leaf and when the larva hatches out, it proceeds to make a mine in the leaf, eating the layer between the top and bottom surfaces of it.

It does this in between two veins, near the base of the leaf where the veins come together. The mine is made during the summer, when the leaf is fully green, but in the autumn, when the tree withdraws its chlorophyll from each leaf in preparation for the leaves’ dying and falling to the ground, the chlorophyll’s route back from the leaf into the sap of the tree is blocked by the mine. This gives rise to the ‘island’ of green colour that is left stranded in the otherwise yellow leaf and from which the micro-moth derives its common name. Such mines are inconspicuous during the summer, and it is only when the leaves change colour in the autumn that they become visible and obvious. The mines can be surprisingly common on some aspen trees, and I find them every autumn when I check any aspen stand with more than a handful of trees in it. I have a growing interest in leaf miners, and this is one of the easiest species to identify, because of the tell-tale ‘green islands’ on the leaves. I have never knowingly seen an adult of this species though.

I continued walking back westwards at the top of the cliffs, past the aspen trees, until I could find a way down to the edge of the loch again. Reaching the loch shore, I noticed a bird on a small gravel bar out in the loch, and when I looked closely at it, I realised that it was the cormorant I’d seen before – it still had the cluster of feathers stuck in its bill. I watched it for a few minutes more, until it took off and flew back to its previous perch on the branch of the aspen tree.

This was obviously a favoured location for the bird, and while I observed it, it was joined there by another cormorant. Excited at seeing a pair together I began to approach them again, in a similar fashion to earlier in the day. However, this time the birds were much more skittish and wouldn’t let me get very close at all. While I was still quite a distance from them, they took off from the aspen branch and landed in the water nearby. They were only there for a couple of minutes though, because as soon as I attempted to get close to them, they lifted off from the water and flew away.

That was the last I saw of them, as they didn’t re-appear during the remainder of the day. However it had been a truly memorable experience for me, featuring one of the closest encounters I’ve ever had with a bird like this in the Caledonian Forest. It was all the more notable because it was the first time I’ve seen a cormorant in Glen Affric or indeed any of the other pinewood remnants that I visit regularly. I took about 400 photographs of it altogether, which has made for a considerable editing job, to reduce those down to the much smaller number of really good images that are worth keeping. I also shot some video footage of the cormorant, and here’s a brief compilation of that to finish this blog with:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgbjypGZ3m8;vq=hd720&rel=0&showinfo=0

Very Nice article and neatly written down the story, Alan!

Yes – a great record.

We see a cormorant regularly over the last several years on the River Till, a few miles over the Border and about 10 miles inland. It is a similar story, with favourite perches and being reasonably tolerant of us – more tolerant perhaps as the years have gone on. This year another one or two cormorants joined the regular bird, and then behaviour was much less tolerant to closer approach.

As a footnote I have seen a pair of greylag geese on the low-lying haugh from time to time over the best part of a decade now. The first time we saw them my two dogs very uncharacteristically ignored them and made no approach and they did not fly off. They have interacted with remaining dog and me over the years, announcing their presence. I have not seen them this year but the last time they circled close directly overhead before we reached the haugh, calling loudly. They repeated this performance further on after we had crossed the haugh and then circled to land in their usual place. As you say it is good to be close up and not to disturb.

Hi Phil, Many thanks for sharing your experience with that cormorant, which sounds like it mirrors mine quite closely. We have lots of pink-footed geese at Findhorn Bay, where I live, and their presence brings a lot of joy to everyone here.

Another lovely blog, Alan.

Thanks Stephen!

Enjoyed this latest news as we were in Glen Affric ourselves in November and marvelled at the autumn colours. We have lived on Skye for thirty two years and think this was the best ever autumn season. Thank you for your interesting articles.

Thanks for the feedback, Pat. Interestingly enough I visited Skye this autumn myself, staying with some friends in their croft at Tokavaig, and I intend to write a blog about that soon. With best wishes, Alan.

Thanks once again for sharing your adventures with us!

Thanks Peggy!

Very nice story Alan. Encounters like that leave you with a warm glow.

Thanks for the feedback, Ron, and yes it was one of those heart-warming experiences in Nature that are so memorable. With best wishes, Alan.